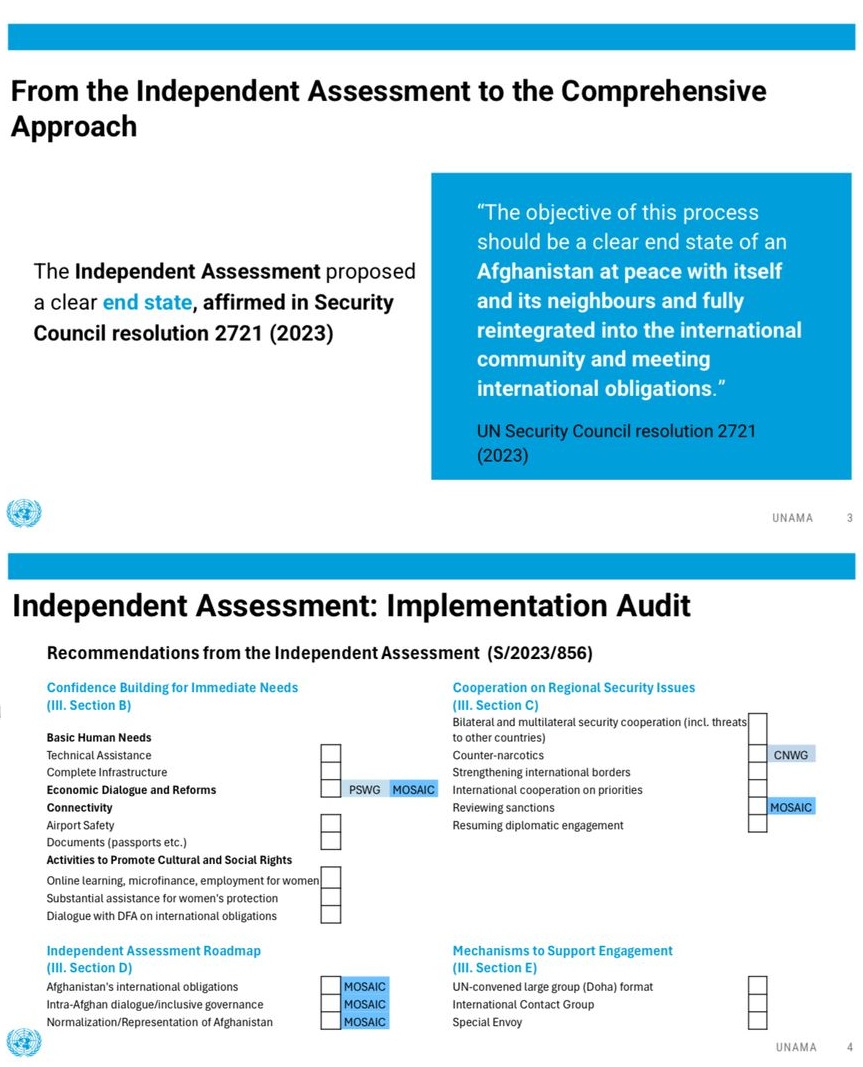

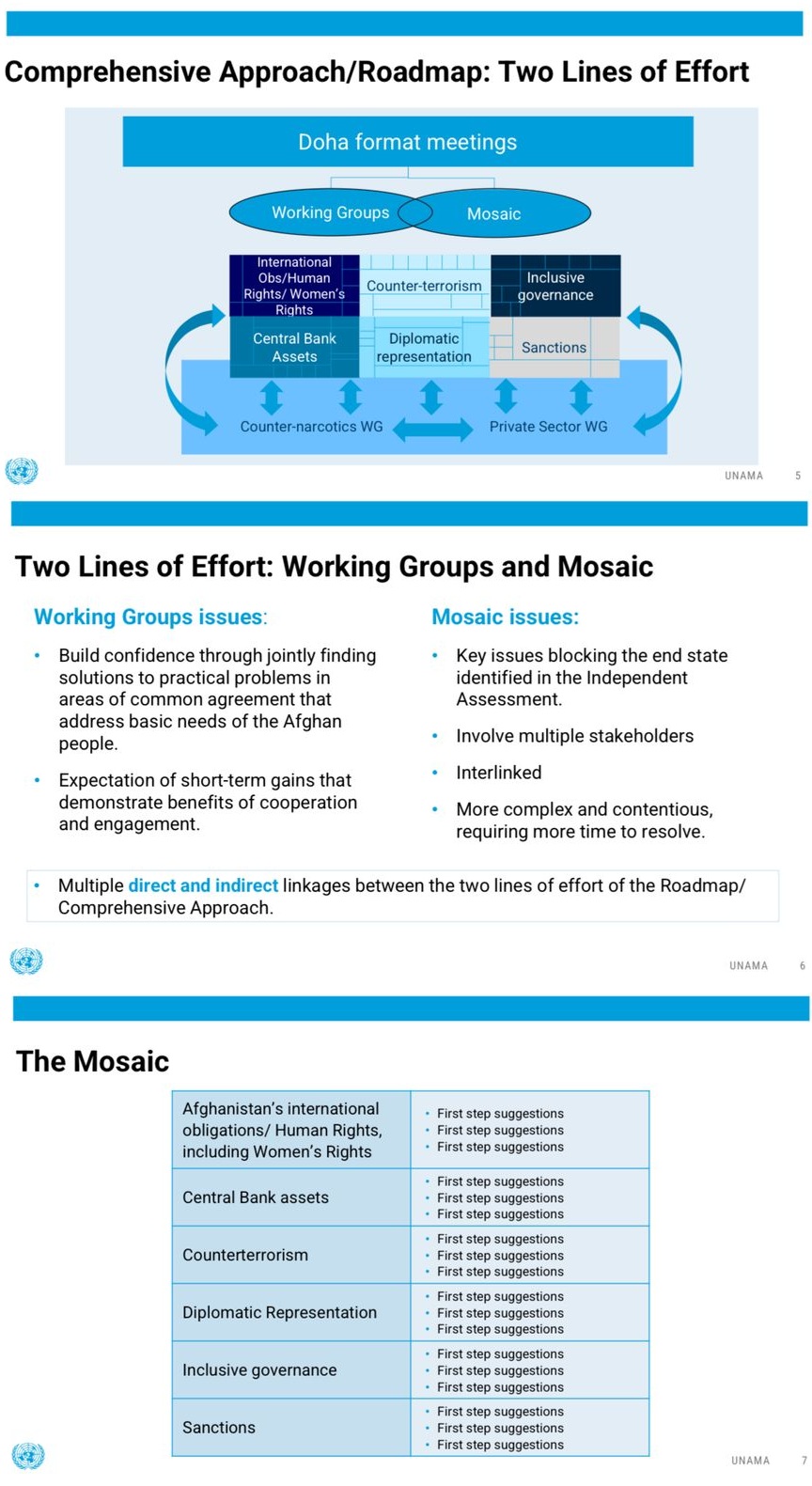

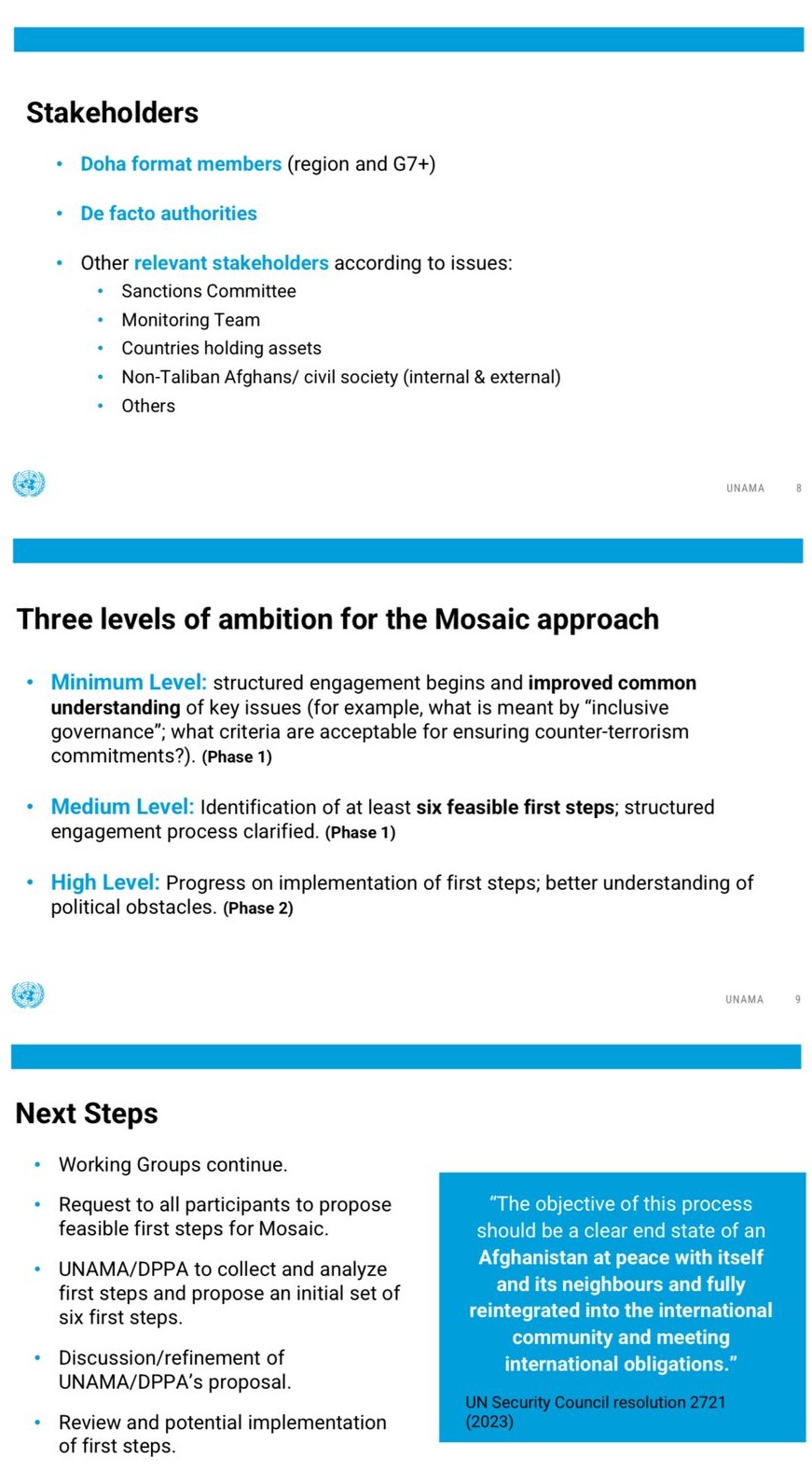

Yet, as of April 2025, one might ask: Can UNAMA point to seven tangible positive achievements since August 2021? While it struggles to highlight successes, its significant failures are harder to ignore—failures it often conceals under various pretexts. Below is a list of ten critical shortcomings that reveal the mission’s challenges in fulfilling its mandate. First, despite UNAMA’s protests, the Taliban enforced the PVPV law, underscoring the mission’s limited influence over key policy decisions. Second, UNAMA declared the expulsion of women from NGOs a “red line,” but Taliban leader Hibatullah crossed it without consequence, exposing the mission’s inability to enforce its stated boundaries. Third, the Doha process proceeded without civil society or non-Taliban representation, despite UNAMA’s objections, further highlighting its marginal role in shaping inclusive dialogue. Fourth, UNAMA lacks direct access to detention centers, relying instead on paid and volunteer informants for information—a makeshift approach that compromises its credibility. Fifth, having lost touch with Afghan civil society, the mission now resorts to convening online discussions with so-called “interlocutors,” a poor substitute for meaningful engagement. Sixth, UNAMA has diluted its push for an inclusive government, redefining it as “inclusive governance.” Under this watered-down standard, hiring a non-Taliban cleric is touted as progress, even as broader representation remains absent. Seventh, caught in the rivalries and dynamism of major global powers, UNAMA has overstepped its mandate. Rather than identifying non-Taliban interlocutors to foster stability and resolve Afghanistan’s crisis, it has aligned itself with competing geopolitical interests. Eighth, the Taliban has repeatedly violated and disrespected UNAMA’s diplomatic immunity, undermining its authority and operational independence. Ninth, fearing reprisals, UNAMA hesitates to invite non-Taliban Afghans to its offices for consultations or meetings. Worse, it has quietly allowed the Taliban’s intelligence department to vet its local staff. This has resulted in a workforce that fails to reflect Afghanistan’s diverse social fabric—ethnic groups, women, and marginalized communities are largely unrepresented. Consequently, UNAMA’s reports and actions fall short of capturing the Taliban’s brutality and the harsh realities of their rule. Finally, tenth, UNAMA now pays the Taliban directly for its security, having canceled contracts with private firms. This arrangement not only allows the Taliban militia to monitor the mission’s activities but also deters non-Taliban Afghans from approaching UNAMA offices, deepening the mission’s isolation. In summary, these failures paint a troubling picture of UNAMA’s effectiveness. Far from advancing stability or amplifying Afghan voices, the mission appears increasingly compromised, disconnected, and beholden to the very forces it was meant to influence. Note: Details of the so-called MOSAIC – a shameful appeasement is in the attachment.